“Truth is image, but there is no image of truth.”

An exploration of the shared histories of cameras, weapons, policing and justice. As surveillance technologies become a fixture in everyday life, the film interrogates the complexity of an objective point of view, probing the biases inherent in both human perception and the lens.

Explore an interactive companion of articles, quotes, links, and archival materials that inspired the 2021 documentary All Light, Everywhere.

“Truth is image, but there is no image of truth.”

“The eye never has enough of seeing, nor the ear its fill of hearing. What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun.”

“We all feel that there is something more. That the curtain has not yet been lifted. There is a prophet within us, forever whispering that behind the seen lies the immeasurable unseen.”

“Archives are the product of a process which converts a certain number of documents into items judged to be worthy of preserving and keeping in a public place, where they can be consulted according to well-established procedures and regulations. As a result, they become part of a special system, well illustrated by the withdrawal into secrecy or ‘closing’ that marks the first years of their life. For several years, these fragments of lives and pieces of time are concealed in the half-light, set back from the visible world. A ban of principle is imposed upon them. This ban renders the content of these documents even more mysterious. At the same time a process of despoilment and dispossession is at work: above all, the archived document is one that has to a large extent ceased to belong to its author, in order to become the property of society at large, if only because from the moment it is archived, anyone can claim to access the content.”

“I am interested in an exchange with my audience, tackling a subject in such a way that it becomes productive and generates a force field via which others can continue to work on it. It is about gaining new access to things: about establishing a mode in which one not only sees something differently through the images, but sees the images themselves differently.”

Page 1, Journal 1.

“As the eye, such the object.”

I think of the pushed-in eyes of statues.

“The ancestry of Plato’s theory of vision, according to which a stream of light or fire issues from the observer’s eye and coalesces with sunlight, is not easily determined. The theory of a visual current coming from the eye has commonly been associated with the Pythagorean school, and in particular with Alcmaeon of Croton (early fifth century B.C.). Of Alcmaeon’s theory of vision Theophrastus writes: ‘And the eye obviously has fire within, for when one is struck [this fire] flashes out.’

Whatever its origins, the theory of intraocular fire reached its full development with Plato (ca. 427-347 b.c.). Plato’s theory of vision was misunderstood as early as the third century B.C. by Theophrastus, who maintained that Plato conceived of two emanations, one from the eye and the other from the visible object, which meet and coalesce somewhere in the intervening space to produce visual sensation. But this description ignores an absolutely essential element in Plato’s theory, namely, daylight, which coalesces with the fireissuing from the eye. Plato presents his theory most fully in the Timaeus:

Such fire as has the property, not of burning, but of yielding a gentle light, they contrived should become the proper body of each day. For the pure fire within us is akin to this, and they caused it to flow through the eyes, making the whole fabric of the eye-ball, and especially the central part(the pupil), smooth and close in texture, so as to let nothing pass that is of coarser stuff, but only fire of this description to filter through pure by itself. Accordingly, whenever there is daylight round about, the visual current issues forth, like to like, and coalesces with it [i.e., daylight] and is formed into a single homogeneous body in a direct line with the eyes, in whatever quarter the stream issuing from within strikes upon any object itencounters outside. So the whole, because of its homogeneity, is similarly affected and passes on the motions of anything it comes in contact with or that comes into contact with it, throughout the whole body, to the soul, and thus causes the sensation we call seeing.

Visual fire emanates from the eye and coalesces with its like, daylight, to form ‘a single homogeneous body’ stretching from the eye to the visible object: this body is the instrument of the visual power for reaching into the space before the eye. The stress in this passage is not on the emission of an effluence from both the eye and the object of vision, but on the formation of a body, through the coalescence of visual rays and daylight, which serves as a material intermediary between the visible object and the eye.

“Unlike Locke and Condillac, Schopenhauer rejected any model of the observer as passive receiver of sensation, and instead posed a subject who was both the site and producer of sensation. For Schopenhauer, following Goethe, the fact that color manifests itself when the observer’s eyes are closed is central. He repeatedly demonstrated how ‘what occurs within the brain,’ within the subject, is wrongly apprehended as occurring outside the brain in the world. His overturning of the camera obscura model received additional confirmation from early nineteenth-century research that precisely located the blind spot as the exact point of entrance of the optic nerve on the retina. Unlike the illuminating aperture of the camera obscura, the point separating the eye and brain of Schopenhauer’s observer was irrevocably dark and opaque.”

[At the exact point where the world meets the seeing of the world, we’re blind.]

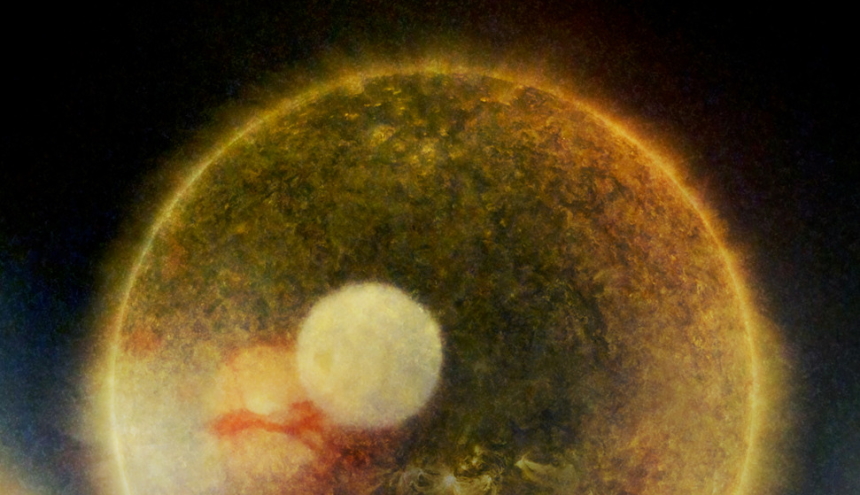

“Turner’s direct confrontation with the sun, however, dissolves the very possibility of representation that the camera obscura was meant to ensure. His solar preoccupations were ‘visionary’ in that he made central in his work the retinal processes of vision; and it was the carnal embodiment of sight that the camera obscura denied or repressed. In one of Turner’s great later paintings, the 1843 Light and Colour (Goethe’s Theory)-The Morning After the Deluge, the collapse of the older model of representation is complete: the view of the sun that had dominated so many of Turner’s previous images now becomes a fusion of eye and sun. On one hand it stands as an impossible image of a luminescence that can only be blinding and that has never been seen, but it also resembles an afterimage of that engulfing illumination. If the circular structure of this painting and others of the same period mimic the shape of the sun, they also correspond with the pupil of the eye and the retinal field on which the temporal experience of an afterimage unfolds. Through the afterimage the sun is made to belong to the body, and the body in fact takes over as the source of its effects. It is perhaps in this sense that Turner’s suns may be said to be self-portraits.”

“We could therefore go so far as to suggest that our visual apparatus introduces edges and cuts into the imagistic flow: it cuts up the environment so that we can see it, and then helps us stitch it back together again. With this idea, we arrive at the concept of perception as active, or even world-making, rather than just secondary and responsive.”

Our original narrator inspiration.

“The concept of dark matter might bring to mind opacity, the color black, limitlessness and the limitations imposed on blackness, the dark, antimatter, that which is not optically available, black holes, the Big Bang theory, and other concerns of cosmology where dark matter is that nonluminous component of the universe that is said to exist but cannot be observed, cannot be recreated in laboratory conditions. Its distribution cannot be measured; its properties cannot be determined; and so it remains undetectable. The gravitational pull of this unseen matter is said to move galaxies. Invisible and unknowable, yet somehow still there, dark matter, in this planetary sense, is theoretical. If the term ‘dark matter’ is a way to think about race, where race, as Howard Winant puts it, ‘remains the dark matter, the often invisible substance that in many ways structures the universe of modernity,’ then one must ask here, invisible to whom? If it is often invisible, then how is it sensed, experienced, and lived? Is it really invisible, or is it rather unseen and unperceived by many? In her essay ‘Black (W)holes and the Geometry of Black Female Sexuality,’ Evelyn Hammonds takes up the astrophysics of black holes found in Michele Wallace’s discussion of the negation of black creative genius to say that if ‘we can detect the presence of a black hole by its effects on the region of space where it is located,’ where, unseen, its energy distorts and disrupts that around it, from that understanding we can then use this theorizing as a way to ‘develop reading strategies that allow us to make visible the distorting and productive effects’ of black female sexualities in particular, and blackness in general. Taking up blackness in surveillance studies in this way, as rather unperceived yet producing a productive disruption of that around it, Dark Matters names the surveillance of blackness as often unperceivable within the study of surveillance, all the while blackness being that nonnameable matter that matters the racialized disciplinary society. It is from this insight that I situate Dark Matters as a black diasporic, archival, historical, and contemporary study that locates blackness as a key site through which surveillance is practiced, narrated, and enacted.”

As we are increasingly surrounded by multiple and expanding wavefronts of calculation, all we are willing to ask from it is to detect patterns or to recover artifacts whose existence is derived from financial models built on technologies of miniaturisation and automation. As a result, techne is becoming the quintessential language of reason, its only legitimate manifestation. Furthermore, instrumental reason, or reason in the guise of techne is increasingly weaponised. Life itself is increasingly construed via statistics, metadata, modelling, mathematics.

If my description of current trends is accurate, then one of the questions a planetary curriculum must ask is the following: What remains of the human subject in an age when the instrumentality of reason is carried out by and through information machines and technologies of calculation?

The second is: Who will define the threshold or set the boundary that distinguishes between the calculable and the incalculable, between that which is deemed worthy and that which is deemed worthless, and therefore dispensable?

The third is whether we can turn these new instruments of calculation and power into instruments of liberation. In other words, will we be able to invent different modes of measuring that might open up the possibility of a different aesthetics, a different politics of inhabiting the Earth, of repairing and sharing the planet?

“Most dictionaries make little semantic distinction between the words ‘observer’ and ‘spectator,’ and common usage usually renders them effectively synonomous. I have chosen the term observer mainly for its etymological resonance. Unlike spectare, the Latin root for ‘spectator,’ the root for ‘observe’ does not literally mean ‘to look at.’ Spectator also carries specific connotations, especially in the context of nineteenth-century culture, that I prefer to avoid-namely, of one who is a passive onlooker at a spectacle, as at an art gallery or theater. In a sense more pertinent to my study, observare means “to conform one’s action, to comply with,” as in observing rules, codes, regulations, and practices. Though obviously one who sees, an observer is more importantly one who sees within a prescribed set of possibilities, one who is embedded in a system of conventions and limitations. And by ‘conventions’ I mean to suggest far more than representational practices. If it can be said there is an observer specific to the nineteenth century, or to any period, it is only as an effect of an irreducibly heterogeneous system of discursive, social, technological, and institutional relations. There is no observing subject prior to this continually shifting field.”

“The prelude for the score that will unfold throughout the film. The cue features our trio of Susan Alcorn (pedal steel guitar), Andrew Bernstein (alto sax), and Owen Gardner (cello). This piece is a collage and rearrangement of a series of structured improvisations where the focus was to mimic the feeling of witnessing a solar eclipse.”

“The basic theme of De radiis stellarum is the universal activity of nature, exercised through the radiation of power or force. “It is manifest,” al-Kindi asserts, ‘that everything in this world, whether it be substance or accident, produces rays in its own manner like a star….Everything that has actual existence in the world of the elements emits rays inevery direction, which fill the whole world.’ This radiation binds the world into a vast network in which everything acts upon everything else to produce natural effects. Stars act upon the terrestrial world; magnets, fire, sound,and colors act on objects in their vicinity. Even words conceived by the mind can radiate power and thus produce effects outside the mind.”

“Surveillance capitalism unilaterally claims human experience as free raw material for translation into behavioral data. Although some of these data are applied to product or service improvement, the rest are declared as a proprietary behavioral surplus, fed into advanced manufacturing processes known as ‘machine intelligence,’ and fabricated into prediction products that anticipate what you will do now, soon, and later. Finally, these prediction products are traded in a new kind of marketplace for behavioral predictions that I call behavioral futures markets. Surveillance capitalists have grown immensely wealthy from these trading operations, for many companies are eager to lay bets on our future behavior.”

“The term ‘personal equation’ slowly gained currency in the broader culture. Its meaning expanded to include a broader set of personal differences that went far beyond the differences noticed by astronomers in thetiming of star transits. Through the course of the century it became a term used to describe personal opinion and bias. The following definition from Webster’s dictionary reveals the complex meaning of the term, ranging from astronomy to everyday judgments:

Personal equation: The difference between an observed result and the true qualities or peculiarities in the observer; particularly the difference, in an average of a largenumber of observations, between the instant when an observer notes a phenomenon,as the transit of a star, and the assumed instant of its actual occurrence; or, relatively,the difference between these instants as noted by two observers. It is usually only a fraction of a second;—sometimes applied loosely to differences of judgment or method occasioned by temperamental qualities of individuals. ”

NASA Goddard Space Flight Center’s Solar Dynamics Observatory

“Yes, even then, when already all was fading, waves and particles, there could be no things but nameless things, no names but thingless names. I say that now, but after all what do I know now about then, now when the icy words hail down upon me, the icy meanings, and the world dies too, foully named. All I know is what the words know, and the dead things, and that makes a handsome little sum, with a beginning, a middle and an end as in the well-built phrase and the long sonata of the dead. And truly it little matters what I say, this or that or any other thing. Saying is inventing. Wrong, very rightly wrong. You invent nothing, you think you are inventing, you think you are escaping, and all you do is stammer out your lesson, the remnants of a pensum one day got by heart and long forgotten, life without tears, as it is wept. To hell with it anyway. Where was I.”

In 2017, Axon re-branded from Taser International to reflect their growing line of products and services. This renovation came with a new mission statement: “Protect Life, Preserve Truth, Accelerate Justice.”

“Can buildings really be innocent shells that do no harm? Isn’t every artificial landscape the diagram of a certain psychological state?”

“The ideal of transparency places a tremendous burden on individuals to seek out information about a system, to interpret that information, and determine its significance. Its premise is a marketplace model of enlightenment—a “belief that putting information in the hands of the public will enable people to make informed choices that will lead to improved social outcomes” (Schudson, 2015). It also presumes that information symmetry exists among the systems individuals may be considering—that systems someone may want to compare are equally visible and understandable. Especially in neoliberal states designed to maximize individual power and minimize government interference, the devolution of oversight to individuals assumes not only that people watch and understand visible systems, but that people also have ways of discussing and debating the significance of what they are seeing. The imagined marketplaces of total transparency have what economists would call perfect information, rational decision-making capabilities, and fully consenting participants. This is a persistent fiction.”

“Black luminosity, then, is an exercise of panoptic power that belongs to, using the words of Michel Foucault, ‘the realm of the sun, of never ending light; it is the non-material illumination that falls equally on all those on whom it is exercised.’ Perhaps, however, this is a light that shines more brightly on some than on others.”

“In the 1790s, Bentham saw “inspective architectures” as manifestations of the era’s new science of politics that would marry epistemology and ethics to show the ‘indisputable truth’ that ‘the more strictly we are watched, the better we behave.’ Such architectures of viewing and control were unevenly applied as transparency became a rationale for racial discrimination. A significant early example can be found in New York City’s 18th century ‘Lantern Laws,’ which required ‘black, mixed-race, and indigenous slaves to carry small lamps, if in the streetsafter dark and unescorted by a white person.’ Technologies of seeing and surveillancewere inseparable from material architectures of domination as everything ‘from a candleflame to the white gaze’ were used to identify who was in their rightful place and who required censure.‘’

“The Panopticon was conceived by Jeremy Bentham in 1786 and then amended and produced diagrammatically in 1791 with the assistance of English architect Willey Reveley. Bentham first came upon the idea through his brother Samuel, an engineer and naval architect who had envisioned the Panopticon as a model for workforce supervision. Pan, in Greek mythology, is the god of shepherds and flocks, the name derived from paien, meaning ‘pasture’ and hinting at the root word of ‘pastoral,’ and in this way the prefix pan- gestures to pastoral power. Pastoral power is a power that is individualizing, beneficent, and ‘essentially exercised over a multiplicity in movement.’ Bentham imagined the Panopticon to be, as the name suggests, all-seeing and also polyvalent, meaning it could be put to use in any establishment where persons were to be kept under watch: prisons, schools, poorhouses, factories, hospitals, lazarettos, or quarantine stations. Or, as he wrote, ‘No matter how different, or even opposite the purpose: whether it be that of punishing the incorrigible, guarding the insane, reforming the vicious, confining the suspected, employing the idle, maintaining the helpless, curing the sick, instructing the willing in any branch of industry, or training the rising race in the path of education.’ Of course, ‘the willing,’ ‘the idle,’ and the so-called rising race might be more able to leave this enclosure at will or by choice than ‘the suspected’ or ‘the incorrigible.’

The Panopticon’s floor plan is this: a circular building where the prisoners would occupy cells situated along its circumference. With the inspector’s lodge, or tower, at the center, his field of view is unobstructed: at the back of each cell, a window, and in its front a type of iron grating thin enough that it would enable the inspector to observe the goings-on in the prisoner cells. The cells in the Panopticon make use of ‘protracted partitions’—where the partitions extend beyond the iron grating that covers the front of the cell—so that communication between inmates is minimized, and making for ‘lateral invisibility.’ In this enclosed institution the watched are separated from the watchers; the inspector’s presence is unverifiable; and there is said to be no privacy for those that are subject to this architecture of control. Security in the Panopticon, as Bentham asserts, is achieved by way of small lamps, lit after dark and located outside each window of the inspection tower, that worked to ‘extend to the night the security of the day’ through the use of reflectors. By employing mirrors in this fashion, a blinding light was used as a means of preventing the prisoner from knowing whether or not the inspection tower was occupied. Power, in the Panopticon, is exercised by a ‘play of light,’ as Michel Foucault put it, and by ‘glance from center to periphery.’

The inspection tower is divided into quarters, by partitions formed by two diameters to the circle, crossing each other at right angles. For these partitions the thinnest materials might serve; and they might be made removeable at pleasure; the height, sufficient to prevent the prisoners seeing over them from cells. Doors to these partitions, if left open at any time, might produce the thorough light, to prevent this, divide each partition into two, at any part required, setting down the one-half at such distance from the other as shall be equal to the aperture of a door. With Bentham’s plan for prison architecture, we can see how light, shadows, mirrors, and walls are all employed in ways that are meant to engender in many a prisoner a certain self-discipline under the threat of external observation, as was its intended function.”

“Pivotal in shaping this score was finding the right approach to one of its main threads, the archival sections with narration by Keaver Brenai. Starting with the “Transit of Venus”, for these sections it was vital to allow ample space for the narration, but to also provide movement and swells of energy to accompany the archival imagery and still photography. This called for a mixture of drone, meanderingly drifting solos, and what I think of as “frantic-ambient” soundscapes.”

″ . . . Axon will offer law enforcement agencies body cameras and a year of premium service for free, the company announced Wednesday. The move appears to serve two purposes. Axon’s decision to dedicate more resources to body cameras allows it to capitalize on an emerging market with huge potential for growth, thanks largely to police reform activism. And by dropping the Taser name, it can shed some of the unsavory connotations associated with a device connected to scores of civilian deaths at the hands of police.”

“Taser International, a company known for arming the nation’s cops with its controversial electroshock weapons, is rebranding and shifting its business model to focus on police body cameras.

When NASDAQ opens on Thursday, Taser International will officially be known as Axon, adopting the name of the company’s body camera division, which launched in 2009. In an effort to further dominate the market, Axon will offer law enforcement agencies body cameras and a year of premium service for free, the company announced Wednesday.”

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Transits of Venus: A Popular Account of Past and Coming Transits, from the First Observed by Horrocks A.D. 1639 to the Transit of A.D. 2012

“The transit of Venus also promised to be scientists’ best hope for solving the problem of standards since it was expected to close a century of debate surrounding the most important constant of celestial mechanics, the solar parallax. A reliable figure for the solar parallax would enable astronomers to determine the distance from the earth to the sun, set the dimensions of the solar system, and using Newton’s law, deduce the masses of the planets. Camille Flammarion, an astronomer and important popularizer of science, argued that with it astronomers would have ‘the meter of the système du monde.’ The astronomer Hervé Faye agreed. The solar parallax was ‘the key to the architecture of the heavens’ and an ultimate ‘touchstone, a precise verification of the theories of celestial mechanics.’ At stake in this moment was nothing less than the determination of ‘the scale of the universe’ and the problem of the plurality of worlds. Still more important, it was connected to philosophical debates about the value of geometric methods in astronomy and the nature of space and time—all lofty issues tied to earthly concerns of governance, national prestige, and military might.”

“In the 1860s the astronomer Charles Wolf built an artificial star machine that recreated, as closely as possible, the experience of observing transit stars. The machine used artificial stars that passed in front of a telescope’s sighting wires and automatically recorded the time of their passage. When an observer saw the artificial star pass in front of the wires and pressed a telegraphic key, the time as noted by the observer was compared against the time automatically recorded by the artificial star.”

Transit of Venus • L’Illustration No. 1764

For more on the cinematographic history of the Transit of Venus, see Simon Starling’s 2012 short film, The Black Drop.

“The personal equation and reaction time were two controversial terms whose exact meaning would be debated for decades. The term ‘reaction time’ was mostly used by experimental psychologists to describe a lag time, of the order of the tenth of a second, between stimulus and response; the term ‘personal equation’ was mostly used by astronomers. Different astronomical observers assessed time differently, and while these assessments showed a remarkable constancy within the same person, when individuals were compared against each other, results often varied by a few tenths of a second. Many astronomers believed that one reason why observers differed in these estimations was due to their different times of reaction. As the terms reaction time and personal equation gained currency, their definitions nonetheless remained in flux well into the twentieth century.”

“Even before the problem of individual differences in observation leaked to the general public, governments across the world became concerned. Napoleon III’s positivistic empire was the first in France to preoccupy itself with these strange divergences. In 1869 the minister of public instruction, Victor Duruy, addressed a letter to the academy charging ‘scientific missionaries’ to go to the end of the world in 1874 ‘to rid observations from the causes of error which so strangely affected those of 1769.’ Despite the ‘sorry state of the country’s finances,’ the French government was able to amass an impressive amount of money and resources to overcome the obstacles that had haunted the observations made in the previous century. The problem, [the French astronomer Hervé] Faye explained, should be solved no matter the cost.

In 1866 the astronomer Charles Delaunay, an opponent of Le Verrier who would replace him as director of the Paris Observatory in 1870, inaugurated the debate in France with an article designed to point out the ‘embarrassment’ of previous observations. According to Delaunay, a ‘black drop’ that mysteriously appeared between Venus and the sun, combined with the problem of irradiation and personal errors in observations, contributed to the astronomers’ ‘embarrassment in trying to determine the precise instant of contact’ and caused an alarming ‘defectiveness of observations.‘’”

Transit of Venus Video 2004

[The act of observation obscures the observation.]

[Where the world meets the image of the world, the image falls apart.]

“Bergson’s earliest criticisms of the cinematographic method arose in the context of astronomy – precisely where these machines were first used and most desired. Janssen had built his photographic revolver to study the transit of Venus, and almost two decades afterwards, Bergson became engaged in a discussion about how precise the timing of these kinds of events could actually be. A common view held that ‘An eclipse, or even better, the transit of Venus across the sun, is an interesting and instructive fact because it is very precise.’ But Bergson offered a different perspective. This moment was set apart from the rest of moving reality by the scientist: ‘It is the astronomer that catches the position of the planet from the continuous curve it traverses.’ The apparent precision in timing this event was simply a construct.”

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, 1761

Samuel Horsley sketch from Royal Society

“Now, in the continuity of sensible qualities we mark off the boundaries of bodies. Each of these bodies really changes at every moment. In the first place, it resolves itself into a group of qualities, and every quality, as we said, consists of a succession of elementary movements. But, even if we regard the quality as a stable state, the body is still unstable in that it changes qualities without ceasing. The body preeminently – that which we are most justified in isolating within the continuity of matter, because it constitutes a relatively closed system – is the living body; it is, moreover, for it that we cut out the others within the whole. Now, life is an evolution. We concentrate a period of this evolution in a stable view which we call a form, and, when the change has become considerable enough to overcome the fortunate inertia of our perception, we say that the body has changed its form. But in reality the body is changing form at every moment; or rather, there is no form, since form is immobile and the reality is movement. What is real is the continual change of form: form is only a snapshot view of a transition. Therefore, here again, our perception manages to solidify into discontinuous images the fluid continuity of the real. When the successive images do not differ from each other too much, we consider them all as the waxing and waning of a single mean image, or as the deformation of this image in different directions. And to this mean we really allude when we speak of the essence of a thing, or of the thing itself.”

“In March 1713, the Common Council of New York City passed a ‘Law for Regulating Negro & Indian Slaves in the Nighttime’ that declared, ‘no Negro or Indian Slave above the age of fourteen years do presume to be or appear in any of the streets’ of New York City ‘on the south side of the fresh water in the night time above one hour after sun sett without a lanthorn and a lighted candle…’

We can think of the lantern as a prosthesis made mandatory after dark, a technology that made it possible for the black body to be constantly illuminated from dusk to dawn, made knowable, locatable, and contained within the city. The black body, technologically enhanced by way of a simple device made for a visual surplus where technology met surveillance, made the business of tea a white enterprise and encoded white supremacy, as well as black luminosity, in law. In situating lantern laws as a supervisory device that sought to render those who could be, or were always and already, criminalized by this legal framework as outside of the category of the human and as un-visible, my intent is not to reify Western notions of ‘the human,’ but to say here that the candle lantern as a form of knowledge production about the black, indigenous, and mixed-race subject was part of the project of a racializing surveillance and became one of the ways that, to cite [Katherine] McKittrick, ‘Man comes to represent the only viable expression of humanness, in effect, overrepresenting itself discursively and empirically,’ and, I would add, technologically.”

“In Baltimore, a city that is 63 percent black, the Justice Department found that 91 percent of those arrested on discretionary offenses like ‘failure to obey’ or ‘trespassing’ were African-American. Blacks make up 60 percent of Baltimore’s drivers but account for 82 percent of traffic stops. Of the 410 pedestrians who were stopped at least 10 times in the five and a half years of data reviewed, 95 percent were black.”

“‘It’s a chance to show our side of the story,’ he said, noting residents often record their own footage of police interactions. ‘That way, if anything goes to court, they have their footage and we have our footage.’

Partee, echoing the stance of Police Commissioner Kevin Davis, said he sees the body cameras as a ‘win-win’ for residents and officers. Kim told the officers, ‘If you do something wrong, that’s what it’s going to catch. If you do something right, that’s what it’s going to catch.‘’

He added, ‘You might change how you talk with that camera on. Everybody does.’”

“This was one of the last pieces of music finalized for the film. I exported all the channels for the Levitation scene and sent them to Theo and he remixed them into a new work for this sequence.”

“Transparency is thus not simply ‘a precise end state in which everything is clear and apparent,’ but a system of observing and knowing that promises a form of control. It includes an affective dimension, tied up with a fear of secrets, the feeling that seeing something may lead to control over it, and liberal democracy’s promise that openness ultimately creates security. This autonomy-through-openness assumes that ‘information is easily discernible and legible; that audiences are competent, involved, and able to comprehend’ the information made visible — and that they act to create the potential futures openness suggests are possible. In this way, transparency becomes performative: it does work, casts systems as knowable and, by articulating inner workings, it produces understanding.”

For the Axon sections, our camera was attached to an electronic stabilizing rig.

Every movement we made was registered and calculated by the on-board computer.

The computer sent out instructions to the motors, which enacted a precise counter-movement to negate any trace of our footsteps.

But we could never get the calibration right. Our footsteps carried through, hovering in an uncanny compromise between human operator and machine interface.

In 2019, Axon released its Axon Body 3 camera. The newer models shoots at a higher resolution, are GPS-enabled, and are equipped to function with Axon’s new suite of automated image and voice recognition systems.

“‘When video allows us to look through someone’s eyes, we tend to adopt an interpretation that favors that person,’ [University of South Carolina law Professor] Seth Stoughton said, explaining a psychological phenomenon known as ‘camera perspective bias.‘’”

There is no single definition of what constitutes a lawful or unlawful use of force. In most departments, the baseline standard by which a use of force is judged is called ‘objectively reasonable.’ The working definition of ‘objectively reasonable’ was established in the landmark 1989 Supreme Court Case Graham v. Connor. In it, the court defines ’objectively reasonable as:

“The “reasonableness” of a particular use of force must be judged from the perspective of a reasonable officer on the scene, rather than with the 20/20 vision of hindsight…. The calculus of reasonableness must embody allowance for the fact that police officers are often forced to make split-second judgments—in circumstances that are tense, uncertain, and rapidly evolving—about the amount of force that is necessary in a particular situation.”

Essentially, this decision states that one must look at what information the officer could have had at the time, and not what someone knows with the benefit of hindsight. The definition offers broad outlines for what constitutes a justifiable use of force, but how this standard gets incorporated into policy is left up to individual departments.

Objectively reasonable provides the minimum standards by which a use of force may be considered justified. However, many recent and highly publicized use of force incidents have been deemed justified in a legal sense but in the eyes of the public are perceived as excessive and unwarranted.

Accordingly, many jurisdictions have begun to shift their thinking when it comes to this standard. After a spike in homicides in 2012, the Camden police chief began a large scale effort at reforming the police department with an emphasis on building community relations. This included a complete and total overhaul of departmental policy, including Use of Force.

“Surveillance video from body cams and dash cams is increasingly used by police organizations to enhance accountability, and yet little is known about their effects on observer judgment. Across eight experiments, body cam footage produced lower judgments of intent in observers than did dash cam footage, in part, because the body cam (vs. dash cam) visual perspective reduces the visual salience of the focal actor.”

“Objectively reasonable provides the minimum standards by which a use of force may be considered justified. However, many recent and highly publicized use of force incidents have been deemed justified in a legal sense but in the eyes of the public are perceived as excessive and unwarranted.

Many jurisdictions have begun to shift their minimum standards from ‘objectively reasonable’ to ‘necessary and proportional.’ The American Law Institute offers a definition for the objective of ‘necessary and proportional’ in a 2017 report:

Officers should not use more force than is proportional to the legitimate law enforcement objective at stake. In furtherance of this objective:

(a) deadly force should not be used except in response to an immediate threat of serious physical harm or death to officers, or a significant threat of serious physical harm or death to others;

(b) non-deadly force should not be used if its impact is likely to be out of proportion to the threat of harm to officers or others or to the extent of property damage threatened. When non-deadly force is used to carry out a search or seizure (including an arrest or detention), such force only may be used as is proportionate to the threat posed in performing the search or seizure, and to the societal interest at stake in seeing that the search or seizure is performed.”

“For television audiences, the [Rodney King] tape’s indexicality was implicitly established and the tape’s vision implied a subject with a common sensibility. In court, the tape did not function as an index that the police involved had broken with authorized procedure. The tape functioned as proof that the beating occurred only insofar as it appeared as a seeing detached from any seeing subject, allowing those present in court to see the beating for themselves. Yet the very marks of historical trauma on the tape, the limitations that give the image its power on television, imply a subject embedded in the situation in which the tape was shot. Entering the tape into evidence rendered those marks irrelevant. The materiality of vision disappears in the process of translating the image into a set of facts. The defense controlled the translation of the tape into facts through the use of testimony. Because the prosecution offered the tape to prove something that was not entirely visible (i.e., the use of excessive force), the defense was able to solicit testimony that the image suggested something else.”

“A continuation of our archival motif first heard in “Transit Of Venus”, “Photographic Revolver” builds on what we had and hints at new sounds and new ideas to come.”

Photographic Atlas of the Sun, Paris Observatory

“Photography compensated for an observer’s attention deficit by permitting astronomers to consult records ‘at ease’ His efforts to eliminate the effects of nervousness, distrac- tion, excitement, and surprise led Faye to discard ‘the ancienne method based on our senses’ and to instead advocate ‘automatic observation’.

Photography should be employed by scientists precisely because it elimi- nated nervous feelings: ‘Here the nervous system of the astronomer is not in play; it is the sun itself that records its transit.’ With photography, Faye claimed, ‘the observer does not intervene with his nervous agitations, anxieties, worries, his impatience, and the illusions of his senses and nervous system.’ Only by ‘completely suppressing the observer’—as photography purportedly did—could astronomers have access to nature itself: ‘[With photography] it is nature itself that appears under your eyes.’”

La Nature - Vol. 3, No. 79

This is a mistake. Janssen’s design was not based on Richard Jordan Gatling’s design for the semi-automatic machine gun, it was based on Samuel Colt’s design for the pistol revolver. See this passage from Paul Virilio’s War and Cinema:

In 1874 the Frenchman Jules Janssen took inspiration from the multi-chambered Colt (patented in 1832) to invent an astronomical revolving unit that could take a series of photographs. On the basis of this idea, Étienne-Jules Marey then perfected his chrono-photographic rifle which allowed its user to aim at and photograph an object moving through space.

Although the lineage is similar in spirit, I have to admit that this is an embarrassing mistake. It’s a situation where one of those foundations of an argument gets adapted so early on that it gets written into every iteration of the idea. Its assumptions become the very fabric of the piece, embedded so deep that you never actually question their veracity.

In tracing this mistake, I was taken back to this write-up of Simon Starling’s excellent film “The Black Drop”, which I encountered early in my research. In it, the author calls Janssen’s invention ‘the Gatling gun of the photographic world.’ This compelling image undoubtedly took hold of me, and as I further researched the failed pacifist aspirations of Gatling, I was emotionally swayed by the potential of this ideological resonance with Janssen and Marey. I wished it to be true, but it’s not. I apologize to any viewers who feel misled by this error. I would especially like to apologize to the author Jimena Canales, whose thinking was so deeply inspirational to this film and especially these historical sections. I can’t help but feel as if this error betrays the relentless integrity of her work which guided us through so many of these sections.

Civil War Images. Plate of Gardner’s Photographic Sketch Book of the War, Vol. 1, Philp & Solomons, Publishers, Washington, DC (1866). This image is cropped from the copy published by the Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division.

Antietam Battlefield From National Park Service

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C.

See also the pioneering work of French astronomer Hervé Faye. From Jimena Canales’ Tenth of a Second:

“Disillusioned by the transitory nature of the ‘fleeting instants of calm which the English astronomers call a glimpse,’ he promoted ‘the simple yet fecund idea of suppressing the observer and of replacing his eye and brain with a sensitive plaque connected to an electrical telegraph.’ In a set of pioneering experiments, he attached a photographic apparatus to a meridian telescope, and, by having an assistant press a key, automatically exposed the photographic film. Using an elaborate clockwork mechanism, he registered by telegraph the time of the ‘spontaneous’ exposure. With ‘the simple movement of a handle’ multiple photographs separated by one-second intervals were recorded in a single plate: ‘Voilà, a completely automatic observation produced under our eyes by a young apprentice who had no idea what he was doing. We could have done it with a machine.’

“In order for Nature to be knowable, it must first be refined, partially converted into (but not contaminated by) knowledge.”

“Transit of Venus”, Pierre Jules César Janssen (1824–1907)

[Where seeing meets the seeing of the world, we’re blind.]

“The competition to establish the precise moment of contact during the transit of Venus was described variously as a ‘lutte pacifique,’ a ‘European debacle,’ and ‘a gigantic scientific tournament.’ While in the 1860s astronomers suggested that different nations work together, the Franco-Prussian War completely eliminated any hopes for international cooperation. The fight for eliminating individual differences was a belligerent and nationalistic competition.”

Thames Advertiser, Volume VII, Issue 1915, 10 December 1874.

“The astronomer Adolph Hirsch complained that ‘each nation had come up with their own solar parallax.’ And the popular science writer Wilfrid de Fonvielle, who had alerted the general public to the discordances of the previous transits of Venus, mocked the astronomers’ hopes. In Le Mètre international définitif he commented cynically on the host of solar parallax values that had resulted from the British, American, French, German, and Russian expeditions: ‘There are as many great nations as there are distances from the sun to the earth. It is terribly irritating that each nation cannot have its own special planet for its own individual use and is obliged to prosaically receive heat from that banal celestial body which illuminates all the others.’”

“The problem of determining inaccessible distances in astronomy, such as deriving the distance from the earth to the sun through observations of the transit of Venus, was militarily pertinent. New artillery proved the need for determining the distance of barely visible and inaccessible targets, and the efforts placed on transit of Venus observations were seen as a subset of this great and mundane concern. In his public lectures on the transit Faye explained how astronomers acted like ‘artillerymen who need to determine the distance of the target if they want to aim in a way to hit it’ and compared the telescope to a ‘cannon.’ The astronomer Charles Wolf also explained the transit in the same military terms. ‘You know,‘’ he wrote, ‘how in the battlefield an officer deduces the distance of the enemy battalion from the angle at which he sees a man, whose average height he knows. This angle is, for the enemy battalion, the parallax of the officer.’ The sentiment of extending scientific and military cooperation resulted in a profound col- laboration between the navy and the Académie during the 1874 transit of Venus expeditions. These concerns continued for decades. The astronomer Janssen, for example, worried about determining inaccessible distances after the Boer war: ‘New infantry and especially artillery weapons’ could reach ‘the enemy in places where he is sometimes barely visible.’”

“The camera as phallus is, at most, a flimsy variant of the inescapable metaphor that everyone unselfconsciously employs. However hazy our awareness of this fantasy, it is named without subtlety whenever we talk about ‘loading’ and ‘aiming’ a camera, about ‘shooting’ a film.

Like guns and cars, cameras are fantasy-machines whose use is addictive. However, despite the extravagances of ordinary language and advertising, they are not lethal. In the hyperbole that markets cars like guns, there is at least this much truth: except in wartime, cars kill more people than guns do. The camera/gun does not kill, so the ominous metaphor seems to be all bluff—like a man’s fantasy of having a gun, knife, or tool between his legs.

Still, there is something predatory in the act of taking a picture. To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed. Just as the camera is a sublimation of the gun, to photograph someone is a sublimated murder—a soft murder, appropriate to a sad, frightened time.”

A Janssen story that didn’t make the cut:

In 1870, the same year he was hard at work on his revolver, Janssen found himself stuck in the city during the Siege of Paris by Prussian forces. The solar eclipse of 1870 was fast approaching. With no other way out, onlookers reported a floating Jules Janssen could be be seen, high above the city, escaping by hot air balloon. Unfortunately, by the time he reached Algeria to view the eclipse, his view was obscured by a cloud.

“Beginning in the late 1500s the figure of the camera obscura begins to assume a preeminent importance in delimiting and defining the relations between observer and world. Within several decades the camera obscura is no longer one of many instruments or visual options but instead the compulsory site from which vision can be conceived or represented. Above all it indicates the appearance of a new model of subjectivity, the hegemony of a new subject-effect. First of all the camera obscura performs an operation of individuation; that is, it necessarily defines an observer as isolated, enclosed, and autonomous within its dark confines. It impels a kind of askesis, or withdrawal from the world, in order to regulate and purify one’s relation to the manifold contents of the now ‘exterior’ world. Thus the camera obscura is inseparable from a certain metaphysic of interiority: it is a figure for both the observer who is nominally a free sovereign individual and a privatized subject confined in a quasi-domestic space, cut off from a public exterior world.”

“Since the beginning of the year, the Baltimore Police Department had been using the plane to investigate all sorts of crimes, from property thefts to shootings. The Cessna sometimes flew above the city for as many as 10 hours a day, and the public had no idea it was there.

A company called Persistent Surveillance Systems, based in Dayton, Ohio, provided the service to the police, and the funding came from a private donor. No public disclosure of the program had ever been made.”

“The American Civil Liberties Union of Maryland published a report today detailing continued officer misconduct in the Baltimore Police Department, despite promises of reform following the 2015 death of Freddie Gray in police custody.

According to the report, complaints were submitted about more than 1,800 officers between 2015 and 2019, a period that coincided with a Department of Justice investigation and the implementation of a federal consent decree. More than 400 officers have been “the subject of at least one complaint of physical violence against a member of the public.”

A complaint is any allegation of misconduct submitted by a resident or internally by the department. The report notes that a complaint ‘does not imply that the officer has committed a crime, or that the officer committed the offense for which the complaint was submitted if it is not listed as sustained.’ The report only lists officers with 15 or more complaints.

According to the police department’s data, available through the law enforcement transparency tool Project Comport, officers who had complaints had an average of 6.5 complaints each between 2015 and 2019.. In the past 12 months, about 20 percent of officers have received complaints, according to the data. The department has about 2,600 officers.”

“Baltimore officials said they cannot provide the emails of a top police commander who oversaw a controversial aerial surveillance program this year because his email account was not configured properly and the records were not retained as required by state law and city policy … The pilot program was not initially disclosed to the public, then-Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake, the City Council, other elected officials, prosecutors or public defenders — many of whom criticized the department for its lack of transparency.”

This unique way to see Brooklyn contrasts directly with the way the city is increasingly recorded and represented today. The advent of GIS and the rise of network protocols have placed virtually all urban imaging and remote sensing systems “on the grid.” Using a flock of birds as one component of an imaging apparatus, this project confronts the limits of this grid by creating an equally rich disclosure of the city: seeing the city as a flock does.

“Now, [Ross] McNutt wants to bring his plane back to Baltimore—with an unusual new pitch. He’s working with residents frustrated with a notoriously corrupt police force in a city that the FBI declared one of the nation’s most violent to drum up support for the surveillance plane’s return.

‘We hold police accountable. We provide unbiased information as to police activities. We can go back in time and see what happened at the scene of an incident,’ McNutt said at a recent public hearing. ‘Just as we can deter potential criminal misconduct, we can also deter potential police misconduct.’”

“But how to link this obsessive policing, division, and representation of ground to the philosophical assumption that in contemporary societies there is no ground to speak of? How do these aerial representations—in which grounding effectively constitutes a privileged subject—link to the hypothesis that we currently inhabit a condition of free fall? The answer is simple: many of the aerial views, 3-D nose-dives, Google Maps, and surveillance panoramas do not actually portray a stable ground. Instead, they create a supposition that it exists in the first place. Retroactively, this virtual ground creates a perspective of overview and surveillance for a distanced, superior spectator safely floating up in the air. Just as linear perspective established an imaginary stable observer and horizon, so does the perspective from above establish an imaginary floating observer and an imaginary stable ground.”

“With this assumption of cybernetics into the heavens, we seem to have moved far away from military cinematography. Yet the innovation of eyeless vision is directly descended from the history of the line of aim. The act of taking aim is a geometrification of looking, a way of technically aligning ocular perception along animaginary axis that used to be known in French as the ‘faith line’ (ligne de foi). Prefiguring the numerical optics of a computer that can recognize shapes, this ‘line of aim’ anticipated the automation of perception–hence the obligatory reference to faith, belief, to denote the ideal alignment of a look which, starting from the eye, passed through the peep-hole and the sights and on to the target object. Significantly, the word ‘faith’ is no longer used in this context in contemporary French: the ideal line appears thoroughly objective, and the semantic loss involves a new obliviousness to the element of interpretative subjectivity that is always in play in the act of looking…

From the original watch-tower through the anchored balloon to the reconnaissance aircraft and remote-sensing satellites, one and the same function has been indefinitely repeated, the eye’s function being the function of a weapon.”

“Structural bias is a social issue first, and a technical issue second.”

“By a process of algebraic cancellation, the negating of subjectivity by the subject became objectivity”

“Linear perspective is based on several decisive negations. First, the curvature of the earth is typically disregarded. The horizon is conceived as an abstract flat line upon which the points on any horizontal plane converge. Additionally, as Erwin Panofsky argued, the construction of linear perspective declares the view of a one-eyed and immobile spectator as a norm—and this view is itself assumed to be natural, scientific, and objective. Thus, linear perspective is based on an abstraction, and does not correspond to any subjective perception. Instead, it computes a mathematical, flattened, infinite, continuous, and homogenous space, and declares it to be reality. Linear perspective creates the illusion of a quasi-natural view to the “outside,” as if the image plane was a window opening onto the “real” world. This is also the literal meaning of the Latin perspectiva: to see through.”

“The scientist has above all things to aim at self-elimination in his judgements, to provide an argument which is as true for each individual mind as for his own.”

“This is the gaze that mythically inscribes all the marked bodies, that makes the unmarked category claim the power to see and not be seen, to represent while escaping representation.”

“Unlike the randomly disturbed grains of analog photography, digital images, such as satellite images, are divided into a grid of equal square units, or pixels. This grid filters reality like a sieve or a fishing net. Objects larger than the grid are captured and retained. Smaller ones pass through and disappear. Objects close to the size of the pixel are in a special threshold condition: whether they are captured or not depends on the relative skill, or luck, of the fisherman and the fish.”

“Transparency concerns are commonly driven by a certain chain of logic: observation produces insights which create the knowledge required to govern and hold systems accountable. This logic rests on an epistemological assumption that ‘truth is correspondence to, or with, a fact.’ The more facts revealed, the more truth that can be known through a logic of accumulation. Observation is understood as a diagnostic for ethical action, as observers with more access to the facts describing a system will be better able to judge whether a system is working as intended and what changes are required. The more that is known about a system’s inner workings, the more defensibly it can be governed and held accountable…

This chain of logic entails ‘a rejection of established representation’ in order to realize ‘a dream of moving outside representation understood as bias and distortion’ toward ‘representations [that] are more intrinsically true than others.’ It lets observers ‘uncover the true essence’ of a system. The hope to ‘uncover’ a singular truth was a hallmark of The Enlightenment, part of what Daston (1992) calls the attempt to escape the idiosyncrasies of perspective: a ‘transcendence of individual viewpoints in deliberation and action [that] seemed a precondition for a just and harmonious society.‘’

“Since I have mentioned video, I ought to point out that the most developed critiques of the illusory facticity of photographic media have been cinematic, stemming from outside the tradition of still photography. With film and video, sound and image, or sound, image, and text, can be worked over and against each other, leading to the possibility of negation and meta-commentary. An image can be offered as evidence, and then subverted. Photography remains a primitive medium by comparison. Still photographers have tended to believe naively in the power and efficacy of the single image. Of course, the museological handling of photographs encourages this belief, as does the allure of the high-art commodity market. But even photojournalists like to imagine that a good photograph can punch through, overcome its caption and story, on the power of vision alone. The power of the overall communicative system, with its characteristic structure and mode of address, over the fragmentary utterance is ignored. A remark of Brecht’s is worth recalling on this issue, despite his deliberately crude and mechanistic way of phrasing the problem:

The muddled thinking which overtakes musicians, writers and critics as soon as they consider their own situation has tremendous consequences to which too little attention is paid. For by imagining that they have got bold of an apparatus which in fact has got hold of them, they are supporting an apparatus which is out of their control.”

“Cameras record from both their ends: the objects, people, and spaces their lenses capture, as well as the position and movements of the invisible photographer. Blurs are important in revealing things about the photographer. Rushed and erratic camera movements might indicate the risk involved in taking some images. A blur is thus the way the photographer gets registered in an image. As such, looking at blurry images is like looking at a scene through a semitransparent glass in which the image of the photographer is superimposed over the thing being photographed.”

10:24 - “The real goal of such an interpretive machine would be to incorporate the reading of an image into the very technology that generates it in the first place, to produce images that arrive before the eye, bearing their own translation into the terms required for intervention, and then to link that directly to the means of intervention.”

“Photography’s power does not reside only in the longed-for invisibility of its producer, but also in the apparent self-presence of its surface. While on the one hand the surface is invisible, a transparent window on to a slice of reality, the surface of the print maps a lie within the image.”

“In the early part of the twentieth century, jurists worried that films could convince a jury without being proved accurate. They resisted admitting films into evidence until a protocol was developed to ensure the truth of what a film showed. At first, judges invoked characteristics of film as a medium to argue for excluding it. Later, they grounded their arguments for what films allow a spectator to know, not what film is. Judges moved from ontological concerns about film to epistemological considerations. The courts were concerned about the unusual persuasiveness of films, that juries would uncritically take the images on screen for facts that ‘speak for themselves,’ and that motion pictures would arrest theflow of speech used to establish the truth at trial. The courts understood evidentiary films as giving a clearer understanding of physical facts than does testimony but required that witnesses testify as to the accuracy of a film presented as evidence. This conception turned the image into an illustration of the speech that guarantees its veracity. By attempting to give film an illustrative rather than a probative role and by grounding the truthfulness of a film in the testimony of the witness authenticating it, the courts tried to screen out any unjustified persuasive force in motion pictures by contextualizing the image in the flow of speech.”

“Courts offered two new definitions for film as a medium: jurists construedfilms either as physical proof (Gulf Life v. Stossel) or as pictorial communication of witness testimony (International Union v. Paul S. Russell). Both kinds had to be authenticated by a testimonial foundation and the credibility of a given film varied according to how that foundation was laid. When an image was presented as proof, witnesses had to attest to its veracity with testimony about its making and projection. When a film was shown as pictorial communication of witness testimony, the medium was not supposed to make it better proof than what could have been said on the stand. Two theories of truth, one based on seeing evidence and the other on hearing testimony, came into conflict. Within this crisis, evidentiary films held the problematic position of an objective form of sight that, unlike cinematic seeing, never implies a seeing subject as its terminus.”

8:30 - “Evidence is precisely that which is not self-evident, it becomes evident only in the eyes and ears of others.”

“We might be tempted to think of this work as a variety of documentary. That is all right as long as we expose the myth that accompanies the label, the folklore of photographic truth. This preliminary detour seems necessary. The rhetorical strength of documentary is imagined to reside in the unequivocal character ofthe camera’s evidence, in an essential realism. The theory of photographic realism emerges historically as both product and handmaiden of positivism. Vision, itself unimplicated in the world it encounters, is subjected to a mechanical idealization. Paradoxically, the camera serves to ideologically naturalize the eye of the observer. Photography, according to this belief, reproduces the visible world: the camera is an engine of fact, the generator of a duplicate world of fetishized appearances, independent of human practice. Photographs, always the product of socially-specific encounters between human-and-human or human-and-nature, become repositories of dead facts, reified objects torn from their social origins.”

“One of the basic requirements of the rule of law is that officials can only be held responsible for violating rules of which they should have been aware . . . Although we leave elected and appointed officials free (within bounds) to do their jobs and apply their expertise, there is a general recognition that those officials work for the public, that what they do should be transparent to the public, and that the public has regular and continuing opportunities (and, to some extent, obligation) to weigh in about how it is governed… One of the reasons accountability is such a concern in policing today is because the existing mechanisms of accountability are focused primarily on the back end, with very little on the front end. Which is to say, existing mechanisms primarily are concerned with identifying and sanctioning misconduct.”

“Vision requires instruments of vision; an optics is a politics of positioning. Instruments of vision mediate standpoints; there is no immediate vision from the standpoints of the subjugated. Identity, including self-identity, does not produce science; critical positioning does, that is, objectivity. Only those occupying the positions of the dominators are self-identical, unmarked, disembodied, unmediated, transcendent, born again. It is unfortunately possible for the subjugated to lust for and even scramble into that subject position–and then disappear from view. Knowledge from the point of view of the unmarked is truly fantastic, distorted, and so irrational. The only position from which objectivity could not possibly be practiced and honoured is the standpoint of the master, the Man, the One God, whose eye produces, appropriates, and orders all difference. No one ever accused the God of monotheism of objectivity, only of indifference. The god-trick is self-identical, and we have mistaken that for creativity and knowledge, omniscience even.”

“Evidentiary film is a repeatable sight that, as it were, stops short of the seeing subject. An evidentiary film does not invite the viewer to ask who is looking. The film’s spectator sees the film from his own point of view, as if the film’s vision terminated in his own consciousness without another in between. Evidentiary films were framed as a seeing that could circulate between subjects without being a subjective point of view. Since the rhetorical force of evidentiary films was based on their objectivity, the scopic field of particular subjects had to be excluded from evidentiary films. For a film to render the point of view of a subject meant that the film was itself subjective. Evidentiary film provided a vision that was objective for each subject that sees it.”

“A quartet of detuned synthesizers bubble along like plastic debris floating down a river unaware that they are pollution incarnate.”

“We no longer look at images-images look at us. They no longer simply represent things, but actively intervene in everyday life. We must begin to understand these changes if we are to challenge the exceptional forms of power flowing through the invisible visual culture that we find ourselves enmeshed within.”

“At least 49 people died in 2018 in the US after being shocked by police with a Taser. In response to mounting public pressure, Axon was forced to drop ‘non-lethal’ from its product descriptions. Today, Axon describes its weapons as ‘less-lethal’, or as ‘electronic control devices (ECDs).‘’”

“The man described for us, whom we are invited to free, is already in himself the effect of a subjection much more profound than himself. A ‘soul’ inhabits him and brings him to existence, which is itself a factor in the mastery that power exercises over the body. The soul is the effect and instrument of a political anatomy; the soul is the prison of the body.”

According to court records, police reports, and news stories from 1983, as well as reports by other organizations, Reuters found that

“The fusion is complete, the confusion perfect: nothing now distinguishes the functions of the weapon and the eye; the projectile’s image and the image’s projectile form a single composite. In its tasks of detection andvacquisition, pursuit and destruction, the projectile is an image or ‘signature’ on a screen, and the television picture is an ultrasonic projectile propagated at the speed of light. The old ballistic projection has been succeeded by the projection of light, of the electronic eye of the guided or ‘video’ missile.”

A 2018 study found that there was no decrease in use of force incidents by police officers wearing body cameras.

18:10 - “What happens in the image guides, produces effect, in the world that is imaged.”

“Images have begun to intervene in everyday life, their functions changing from representation and mediation, to activations, operations, and enforcement. Invisible images are actively watching us, poking and prodding, guiding our movements, inflicting pain and inducing pleasure. But all of this is hard to see.”

“Things are liars which tell the truth”

“This variation on the archival motif comes with a more somber heaviness to it despite a glimmer of light.”

Collège de France, Legs Marey, 1905

College de France, Legs Marey, 1905

College de France, Legs Marey, 1905

College de France, Legs Marey, 1905

Collège de France, Legs Marey, 1905

Cinémathèque Française

Mouette en vol. Obtenu, 1882

Cinémathèque Française

#missingfile

Cinémathèque Française

Cinémathèque Française

“Part of what Marey thinks he can accomplish by presenting in this way the events he investigates becomes clear when he describes the aim of the graphic method: ‘In the laboratory, as at the bed of patients, too much was left up to personal competency, to trained touch, to the subtlety of sense. To render accessible to all the study of the phenomena of life, of these movements so light, so fugitive, of these changes of state so slow or so rapid that they escape the senses, it is necessary to give them an objective form and to fix them under the eye of the observer, so that the observer may study and compare them at leisure. Such is the aim of la méthode graphique.‘’”

Cinémathèque Française

“We were curious to see what expressions the features of a man’s face took on, when he loudly shouted an interjection. The watchman of the physiological station [Marey’s research facility] was the subject of our experiment. Placed before the lens, he called to us several times. The series of images we obtained showed the periodic repetition of the same aspects of the face, but with it so strangely contracted that it seemed a suite of very ugly grimaces. Nonetheless, to see him speak, there was nothing extraordinary in this man’s expression… Let us put these images in a zoetrope and watch them pass before our eye while the instrument turns at an appropriate speed; all the strangeness disappears, and we only see a man who speaks with the most natural appearance. What is there to say? Wouldn’t the ugly only be the unknown, and perhaps the truth wounds our gaze when we behold it for the first time?”

“The visualized data exist only because of the registration situations Marey contrived, and they can be understood only as products of Marey’s artifices, not as superior versions of what observers might learn on their own. The incommensurability between these data and the findings of human sense is such that Marey likens his instruments to new senses: ‘Not only are these instruments sometimes destined to replace the observer, and in such circumstances to carry out their role with an incontestable superiority; but they also have their own domain where nothing can replace them. When the eye ceases to see, the ear to hear, the touch to feel, or indeed when our senses give deceptive appearances, these instruments are like new senses of astonishing precision.’ The distinction between human sense and machine-made visualization relates itself clearly to the present discussion’s main concern. In considering the registration situations Marey contrived for the study of imperceptible forces and displacements, we have to think about the standards and concerns that led him to establish these situations in the particular ways he did.”

Cinémathèque Française

Cinémathèque Française

Cinémathèque Française

“This fact ultimately provides us with a way to approach one of the most striking discrepancies between Bertillon’s project and the endeavor of Marey. While both problematized, in different ways, the relation between photography and what we see, the actual images that issued from Bertillon’s work had a prosaic appearance in comparison with Marey’s. One way to think about this distinction centers on the more adventurous duties that Marey assigned his images vis-à-vis human mental work and synthesis. Marey’s images, clearly, have a more striking aspect than do Bertillon’s. Of the many reasons why this situation should arise, the different ways that Bertillon and Marey strive to make synthetic photographs bears much of the responsibility. Bertillon means his images to find a place within a lawful order, the nature of which the human mind has already established; Marey means his to help generate such an order on their own, to do something that, in Pierce’s words, stands in for human ‘intelligence and genius.’”

“Information machines are the sole means of vision in digital visual culture, but as the body itself becomes socially defined and handled as information, there is even more at stake in paying attention to the incursions of machines in everyday life and the forms of resistance available to us.”

“Now I know I must be on my guard against Cinema. It has made a pact with the future, joined hands to prevent our existence. Cinema takes the side of the image against the honor of the event.”

Cinémathèque Française

“Marey’s interest in disclosing the successive phases of a body movement here becomes a concern to explain the sequence of a sudden disintegration of the landscape which is not fully visible to any one person. Aerial photography, cinematic photogrammetry–once again we find a conjunction between the power of the modern war machine, the aeroplane, and the new technical performance of the observation machine. Even though the military film is made to be projected on screen, thus obscuring the practical value of the successive negatives in analysing the phases of the movement in question, it is fundamentally a reversal of Marey’s or Muybridge’s work. For the point is no longer to study the deformations involved in the movement of a whole body, whether horse or man, but to reconstitute the fractured lines of the trenches, to fix the infinite fragmentation of a mined landscape alive with endless potentialities.”

According to Marey, “The highest point that the natural sciences can reach is the discovery of the laws that govern the phenomena of life.” The laws with the widest application to the phenomena of life, in that they allow investigators to treat the largest set of allied facts, bear on how the “animated motor” uses energy in order to accomplish deeds and perform labor.

“The crisis afflicted the graphic method in general, culminating in a contentious crusade against it in the Académie de médecine. One researcher fought against the ‘pretension that the graphic method should be the starting point of all exact and certain science.’ This opponent of Marey argued that physiological phenomena, including the horse’s gallop, could be grasped in a better way without complicated ‘self-registering’ apparatuses. Traces, he argued, simply lacked ‘imitative harmony.’ Furthermore, interpreting the graphs was as contentious as observing a galloping horse: ‘In examining with attention the traces, one confronts to similar degree the same difficulties that when in the presence of an animal which trots or gallops. . . . These lines tell you nothing.’ Marey was accused of ignoring the fact that graphic traces themselves had to be ‘read,’ and that this introduced some of the same challenges of direct observations: ‘The registering apparatus does nothing but to inscribe undulating lines that fall on our senses; but once it comes to interpreting the traces, the graphic method has no more certitude than direct observation.’ His contradictor contested the supposed universality of their language: ‘If everyone can produce these traces, not everyone is capable of interpreting them.’ After listening to these accusations, even some of the graphic method’s most hardened supporters came to doubt the claim that they constituted a universal, easily interpretable language. An observer concluded: ‘In the sciences of observation, all instruments, no mater how simple or complicated, are aids . . . that speak a special language. Before using them, one must strive to learn their language.‘’”

“I think that images actively used as part of manipulation mean we are no longer concerned with re-presentation but presentation. Images are a part of the primary intervention into the world. In that world, which is more engineering or surgery or sampling, the fundamental question is not, as with the class from particule physics: ‘Does this exist?’ Instead, it’s ’Does our evidence demonstrate to a reasonable probability that there are particles of the type that we’ve described?”

“Photography does not reproduce data in such images, but instead it produces them.”